The industrial design major at Pennsylvania College of Technology is intended to elicit students’ creative potential. For three students on the cusp of graduation, that goal has been met, as evidenced by their senior projects.

Nicole Bamonte, of Williamsport; Nina M. Hadden, of Murrysville; and Abigail M. Meredick, of Danville, have spent countless hours during the past several months drawing on their education and practical experiences to develop prototypes of marketable products. The results are three inspired creations: a collapsible dresser, dog training system and surgical instrument.

“Senior projects are important because they let students pursue their passion in a manner that ensures a commercially viable design,” said Thomas E. Ask, professor of industrial design. “Capstone projects allow the student to represent much of their education in a single design. Education fueled by personal interest is a powerful combination.”

“Senior projects are important because they let students pursue their passion in a manner that ensures a commercially viable design,” said Thomas E. Ask, professor of industrial design. “Capstone projects allow the student to represent much of their education in a single design. Education fueled by personal interest is a powerful combination.”

Bamonte and Meredick enjoyed art classes in high school and began college studying graphic design. Hadden was in the National Art Honor Society and competed on her school’s FIRST Robotics Club team. Eventually, all three discovered that industrial design offered the best path to combine their artistic sensibilities and passion for hands-on, functional design.

“It’s a really good field for people who like art but don’t necessarily want to go into the fine arts or for technical people who don’t want to be engineers,” Hadden said. “Industrial design is in the middle.”

“I wanted to do more than aesthetic treatments, more than two-dimensional art,” Bamonte said. “I wanted to move into three-dimensional structure and build things that are useful.”

“That’s why industrial design is a good field,” Meredick said. “It brings art and building together.”

Meredick hopes her combination of “art and building” benefits the medical community. She’s been working with Dr. John Bailey, an orthopedic surgeon at UPMC Susquehanna, to develop an adjustable cutting guide for use in total knee replacements.

Her approximately 3-inch-long device would reduce the number of pinnings made to the femur during knee replacement surgery. Cutting blocks pinned to the bone often have to be adjusted throughout surgery. The removal of the blocks and repinning results in additional holes and trauma to the bone. With Meredick’s creation, the cutting block can be altered to the desired angle without removing the original pinning. The result is less damage to the femur.

“I’ve gone through numerous prototypes and designs,” said Meredick, who watched two knee surgeries to prep for her project. “I went from super complicated to super simple. Thankfully, I ended up with something that seems to be working out. The plastic prototype worked when we performed a mock-up surgical procedure.

“I’ve gone through numerous prototypes and designs,” said Meredick, who watched two knee surgeries to prep for her project. “I went from super complicated to super simple. Thankfully, I ended up with something that seems to be working out. The plastic prototype worked when we performed a mock-up surgical procedure.

“The hope is we can get our foot into the market and have it manufactured, so it can be used in surgery.”

“Medical products need to be developed with great care, and Abby has done a good job of working through several design options to arrive at her final one,” Ask said. “It is stressful work, and she has handled it with aplomb.”

“A lot has to go into it in order to make the right product,” Meredick said. “It’s not about you. It’s about the consumer or the client.”

That was an important lesson for Bamonte. She hoped to integrate color into her collapsible dresser design. Focus groups convinced her to scrap that idea because specific colors could limit the intended universal appeal of the product.

“It’s not a piece of furniture just for men or just for women,” Bamonte said. “It’s a piece of furniture for all. It’s utilitarian.”

Struggling to move her cumbersome dresser into an apartment prompted Bamonte to create a collapsible one made of wood. Her idea relies on telescoping like a tent pole. The half-inch-thick telescoping cuts through the 40-by-20-by-60-inch dresser and allows it to collapse vertically and horizontally.

“I first started on a really small scale with popsicle sticks to see what would work,” she said. “Then I used drying racks. I moved on to using yellow pine wood for the model. “It’s not made out of expensive material. The perfect place for something like this to be sold at would be IKEA.”

“Designing for a specific market has many advantages that Nicole is trying to exploit,” Ask said. “She identified a demographic that wants light, portable and easy-to-assemble furniture. She has used qualitative methods to tune in her design effectively.”

Like Bamonte, personal experience inspired Hadden’s project, dubbed “The Whiff Board.” Hadden is a dog lover who has engaged in basic obedience and agility training with several four-legged friends. She recognized the need for a scent identification game that could teach house dogs a “cool trick” and be a useful training device for working dogs.

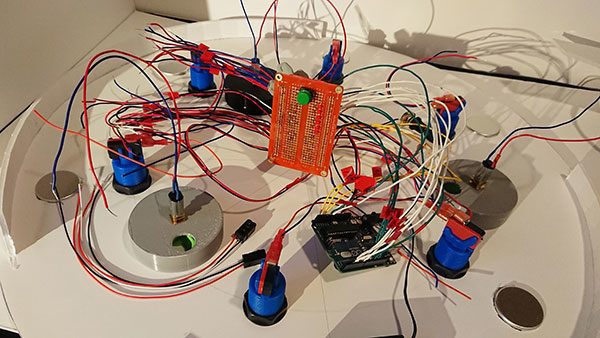

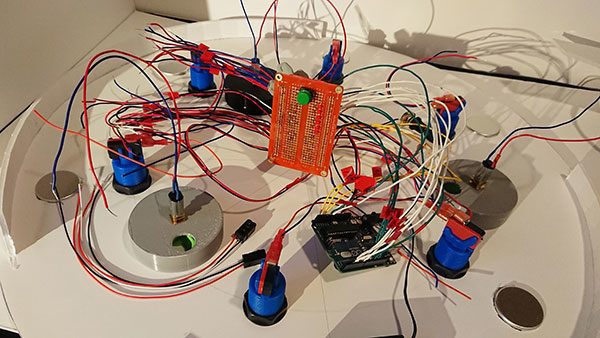

Her system consists of scent cups – each filled with different substances – and arcade-style press buttons. Dogs are instructed to identify a particular scent among the cups and to press the button that corresponds to the desired scent. If they are correct, a treat is distributed to them through an internal chute.

“It takes some of the human interaction with the dog out of it,” Hadden said. “Ideally, when you train a dog, you don’t want the treat to come from you. You want it coming from the source of the good thing they just did. I haven’t seen a system like this out in the market, especially for both civilian and working dogs. There are a lot of dog training companies that make training aids. Maybe one of those companies will be interested in this.”

“It takes some of the human interaction with the dog out of it,” Hadden said. “Ideally, when you train a dog, you don’t want the treat to come from you. You want it coming from the source of the good thing they just did. I haven’t seen a system like this out in the market, especially for both civilian and working dogs. There are a lot of dog training companies that make training aids. Maybe one of those companies will be interested in this.”

“Designing for nonhumans is difficult,” Ask said. “Nina is breaking new ground with her work, and it is very challenging to do research and design validation in this application. She has done a great job juggling ambiguity and design.”

While the three projects are distinct, the students shared similar resources to produce their prototypes. They all utilized modeling, computer-aided-design programs, and various college facilities, such as the industrial design studio, the machine shop and the Dr. Welch Workshop (the campus makerspace).

Reliance on multiple tools, materials and processes is common in the industrial design field, according to Ask. That’s just one reason the senior project serves as valuable, final preparation for the workforce.“Senior projects strive to represent real-world design problems, and they require a complete and appropriate solution,” Ask said. “This is what professional designers do and what the market demands. Therefore, students get to demonstrate their ability to design in the context of real- world applications.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median annual wage for commercial and industrial designers was $66,590 in May 2018.

Information about the industrial design baccalaureate major and other programs offered by the college’s School of Industrial, Computing & Engineering Technologies is available by calling 570-327-4520.

For more on Penn College, a national leader in applied technology education and workforce development, email the Admissions Office or call toll-free 800-367-9222.

Nicole Bamonte, of Williamsport; Nina M. Hadden, of Murrysville; and Abigail M. Meredick, of Danville, have spent countless hours during the past several months drawing on their education and practical experiences to develop prototypes of marketable products. The results are three inspired creations: a collapsible dresser, dog training system and surgical instrument.

“Senior projects are important because they let students pursue their passion in a manner that ensures a commercially viable design,” said Thomas E. Ask, professor of industrial design. “Capstone projects allow the student to represent much of their education in a single design. Education fueled by personal interest is a powerful combination.”

“Senior projects are important because they let students pursue their passion in a manner that ensures a commercially viable design,” said Thomas E. Ask, professor of industrial design. “Capstone projects allow the student to represent much of their education in a single design. Education fueled by personal interest is a powerful combination.”Bamonte and Meredick enjoyed art classes in high school and began college studying graphic design. Hadden was in the National Art Honor Society and competed on her school’s FIRST Robotics Club team. Eventually, all three discovered that industrial design offered the best path to combine their artistic sensibilities and passion for hands-on, functional design.

“It’s a really good field for people who like art but don’t necessarily want to go into the fine arts or for technical people who don’t want to be engineers,” Hadden said. “Industrial design is in the middle.”

“I wanted to do more than aesthetic treatments, more than two-dimensional art,” Bamonte said. “I wanted to move into three-dimensional structure and build things that are useful.”

“That’s why industrial design is a good field,” Meredick said. “It brings art and building together.”

Meredick hopes her combination of “art and building” benefits the medical community. She’s been working with Dr. John Bailey, an orthopedic surgeon at UPMC Susquehanna, to develop an adjustable cutting guide for use in total knee replacements.

Her approximately 3-inch-long device would reduce the number of pinnings made to the femur during knee replacement surgery. Cutting blocks pinned to the bone often have to be adjusted throughout surgery. The removal of the blocks and repinning results in additional holes and trauma to the bone. With Meredick’s creation, the cutting block can be altered to the desired angle without removing the original pinning. The result is less damage to the femur.

“I’ve gone through numerous prototypes and designs,” said Meredick, who watched two knee surgeries to prep for her project. “I went from super complicated to super simple. Thankfully, I ended up with something that seems to be working out. The plastic prototype worked when we performed a mock-up surgical procedure.

“I’ve gone through numerous prototypes and designs,” said Meredick, who watched two knee surgeries to prep for her project. “I went from super complicated to super simple. Thankfully, I ended up with something that seems to be working out. The plastic prototype worked when we performed a mock-up surgical procedure.“The hope is we can get our foot into the market and have it manufactured, so it can be used in surgery.”

“Medical products need to be developed with great care, and Abby has done a good job of working through several design options to arrive at her final one,” Ask said. “It is stressful work, and she has handled it with aplomb.”

“A lot has to go into it in order to make the right product,” Meredick said. “It’s not about you. It’s about the consumer or the client.”

That was an important lesson for Bamonte. She hoped to integrate color into her collapsible dresser design. Focus groups convinced her to scrap that idea because specific colors could limit the intended universal appeal of the product.

“It’s not a piece of furniture just for men or just for women,” Bamonte said. “It’s a piece of furniture for all. It’s utilitarian.”

Struggling to move her cumbersome dresser into an apartment prompted Bamonte to create a collapsible one made of wood. Her idea relies on telescoping like a tent pole. The half-inch-thick telescoping cuts through the 40-by-20-by-60-inch dresser and allows it to collapse vertically and horizontally.

“I first started on a really small scale with popsicle sticks to see what would work,” she said. “Then I used drying racks. I moved on to using yellow pine wood for the model. “It’s not made out of expensive material. The perfect place for something like this to be sold at would be IKEA.”

“Designing for a specific market has many advantages that Nicole is trying to exploit,” Ask said. “She identified a demographic that wants light, portable and easy-to-assemble furniture. She has used qualitative methods to tune in her design effectively.”

Like Bamonte, personal experience inspired Hadden’s project, dubbed “The Whiff Board.” Hadden is a dog lover who has engaged in basic obedience and agility training with several four-legged friends. She recognized the need for a scent identification game that could teach house dogs a “cool trick” and be a useful training device for working dogs.

Her system consists of scent cups – each filled with different substances – and arcade-style press buttons. Dogs are instructed to identify a particular scent among the cups and to press the button that corresponds to the desired scent. If they are correct, a treat is distributed to them through an internal chute.

“It takes some of the human interaction with the dog out of it,” Hadden said. “Ideally, when you train a dog, you don’t want the treat to come from you. You want it coming from the source of the good thing they just did. I haven’t seen a system like this out in the market, especially for both civilian and working dogs. There are a lot of dog training companies that make training aids. Maybe one of those companies will be interested in this.”

“It takes some of the human interaction with the dog out of it,” Hadden said. “Ideally, when you train a dog, you don’t want the treat to come from you. You want it coming from the source of the good thing they just did. I haven’t seen a system like this out in the market, especially for both civilian and working dogs. There are a lot of dog training companies that make training aids. Maybe one of those companies will be interested in this.”“Designing for nonhumans is difficult,” Ask said. “Nina is breaking new ground with her work, and it is very challenging to do research and design validation in this application. She has done a great job juggling ambiguity and design.”

While the three projects are distinct, the students shared similar resources to produce their prototypes. They all utilized modeling, computer-aided-design programs, and various college facilities, such as the industrial design studio, the machine shop and the Dr. Welch Workshop (the campus makerspace).

Reliance on multiple tools, materials and processes is common in the industrial design field, according to Ask. That’s just one reason the senior project serves as valuable, final preparation for the workforce.“Senior projects strive to represent real-world design problems, and they require a complete and appropriate solution,” Ask said. “This is what professional designers do and what the market demands. Therefore, students get to demonstrate their ability to design in the context of real- world applications.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median annual wage for commercial and industrial designers was $66,590 in May 2018.

Information about the industrial design baccalaureate major and other programs offered by the college’s School of Industrial, Computing & Engineering Technologies is available by calling 570-327-4520.

For more on Penn College, a national leader in applied technology education and workforce development, email the Admissions Office or call toll-free 800-367-9222.